If you are interested in knowing more about Coll or the 10 other Irishmen I wrote about in my book (published last year, an Irish best-seller) - have a look here -

Murder, Mutiny & Mayhem - The Blackest Hearted Villains From Irish History - O'Brien Press

Cheers - Joe

Vincent Mad Dog Coll – Hit Man, Child Killer, Original Gaeilgeoir Gangster.

* Vincent Coll was, in some ways, a man born out of his time.

In the seventeenth & eighteenth century, young Irishmen who displayed a talent for killing, plunder and betrayal were as likely to be celebrated in ballads and rewarded by kings as hung from the nearest gallows.

In his brief but blazing career as a killer, bootlegger, kidnapper, shake-down artist, hijacker and hitman-for-hire, the young man labelled ‘Mad Dog’ and ‘Child Killer’ by a mayor of New York, more than earned his place amongst the most notorious Irishmen in history.

In the seventeenth & eighteenth century, young Irishmen who displayed a talent for killing, plunder and betrayal were as likely to be celebrated in ballads and rewarded by kings as hung from the nearest gallows.

In his brief but blazing career as a killer, bootlegger, kidnapper, shake-down artist, hijacker and hitman-for-hire, the young man labelled ‘Mad Dog’ and ‘Child Killer’ by a mayor of New York, more than earned his place amongst the most notorious Irishmen in history.

POSTER FOR A MOVIE BASED ON COLL (1962)

Coll, who was born in Donegal in 1908, was a killer that even the Mafia feared. He might not have been much of a student of the past, but if the young Vincent had paid attention to the Irish priests in the Catholic Reform Schools of New York, or heard on the streets of the Bronx about the history of Irish gangs of the Five Points, Hell’s Kitchen and beyond, he might have seen himself as the last expression of a long and bloody tradition stretching back to the original Irish gangs of New York.

They had been arriving in their hundreds of thousands, even

before the Famine.

And like many immigrant groups, the Irish gradually became part of their adopted city and began to organise politically, securing power and influence in city and state politics, in the police and fire departments and other areas of the New York power structure.

And like many immigrant groups, the Irish gradually became part of their adopted city and began to organise politically, securing power and influence in city and state politics, in the police and fire departments and other areas of the New York power structure.

However, at the same time, the criminal gangs who

controlled gambling, prostitution, the protection-rackets and other enterprises, would continue to

grow with the Big Apple.

The Irish gangs were in many ways a response to the social and economic obstacles facing them on arrival in New York, where they found themselves right at the bottom of the food chain when it came to jobs and political influence (if we don’t include the African-American slaves of the era before the Civil War).

Before the War Between the States and

the rapid expansion to the West, the Irish were compelled to gang up together to get their

own slice of the crowded Big Apple.

And if the ‘nativist’ political structure wouldn’t give them an even break, they would take one for themselves.

And if the ‘nativist’ political structure wouldn’t give them an even break, they would take one for themselves.

But by the time Vincent Coll arrived in New

York, just one year old and with a large family who hoped to escape the grinding poverty of the

Irish-speaking district of Gweedore in north Donegal, his countrymen were beginning to move off the

bottom rung; the Irish in the city were changing, gaining respectability, leaving the crowded

tenements and finding space in the new suburbs growing up around the city as the early 1900s

brought fresh waves of immigrants, from Italy, Eastern and Central Europe and Tsarist Russia and

Poland to the city.

Coll and his family would never get the chance to join this move towards new

horizons. The youngster would become associated with one of the remnants of the earlier days of

New York when he ended up running

with a venerable Irish street gang called the Gophers. With the Irish now associated with business, local government, the NYPD and the Fire Department, moving towards respectability, Vincent would make his name amongst the next generation of criminals, the Jewish and Italian gangsters who made prohibition-era New York rattle to the sound of the Tommy gun.

The Jews and Italians would have to carve out their own territory in New York. And just as the Irish had done before them, most worked hard, organised their communities, gave their children whatever education they could afford and sought out the American Dream. Some choose a quicker route to prosperity. And the nexus point for Jewish, Italian and Irish criminals were gangs like Murder, Incorporated, the name given by the press to what criminal figures also called The Brownsville Boys or The Combination, a loose affiliation of Irish, Jewish and Italian hit-men for hire.

with a venerable Irish street gang called the Gophers. With the Irish now associated with business, local government, the NYPD and the Fire Department, moving towards respectability, Vincent would make his name amongst the next generation of criminals, the Jewish and Italian gangsters who made prohibition-era New York rattle to the sound of the Tommy gun.

The Jews and Italians would have to carve out their own territory in New York. And just as the Irish had done before them, most worked hard, organised their communities, gave their children whatever education they could afford and sought out the American Dream. Some choose a quicker route to prosperity. And the nexus point for Jewish, Italian and Irish criminals were gangs like Murder, Incorporated, the name given by the press to what criminal figures also called The Brownsville Boys or The Combination, a loose affiliation of Irish, Jewish and Italian hit-men for hire.

In the popular narrative of the Gangster era, the

Irish provided the muscle while the Italians and Jews ran the show. But in reality, the times

offered equal opportunities for men of all ethnic backgrounds to find a niche based on their particular

skill-sets. Some gangsters with Irish backgrounds, like Owney Madden, boss of Hell’s Kitchen,

would rise to the top and even achieve a certain sort of glamour (Madden ran the famous Cotton Club

in New York). Some Jewish crime figures, like Mendy Weiss, were out and out killers. And

some, such as Benjamin ‘Bugsy’ Siegel, would combine killing with upper-management

responsibilities.

New York in the Prohibition era was a hot-house for criminal activity. The Federal Government was trying to enforce a deeply unpopular, virtually unworkable law banning the sale of alcohol.

New York in the Prohibition era was a hot-house for criminal activity. The Federal Government was trying to enforce a deeply unpopular, virtually unworkable law banning the sale of alcohol.

Most and local politicians, police chiefs, business

leaders and opinion makers believed the Volstead Act to be, at best, an unenforceable law that

simply pushed regular citizens into the arms of criminals. For the nascent criminal networks of the US,

prohibition was sent from heaven to make them incredibly rich and powerful, putting them at the

centre of a web of crime and influence involving ordinary citizens, corrupt politicians, policemen

and lawyers.

Vincent Coll, with his personality and skill-set, was in the right place at the right time.

Vincent Coll, with his personality and skill-set, was in the right place at the right time.

Police Line-Up Of The Coll Crew - Vincent, tall and dapper as usual, flanked by; Pasquale "Patsy" Del Greco, Dominick Odierno and Frank Gordano. All hired guns.

***************************************

He had been born Uinseann Ó Colla on 20 July 20 1908 above a pub in Gweedore, north Donegal (the pub, Tigh Hiudai Beag, would be the future home of the family that gave us the famous Irish music groups Clannad and Altan). Long after his death, Uinseann, a infamous local boy made bad across the sea, would be known to the people of that part of Donegal as ‘An Madra Mire’, Gaelic for ‘The Mad Dog’.

When Vincent was not quite a year old his father, Toaly Coll, decided to move the family, his wife and seven children to New York in search of a better life. That better life never happened for the Colls. After settling in the Bronx in 1909, they remained trapped in dire poverty. Five of Vincent’s six siblings died before he was twelve. His mother died of TB in 1916, worn out after years of trying to provide for her children. Vincent’s father Toaly had simply run off years before and was never heard from again.

Needless to say, in such an unforgiving world, Vincent was fighting for his life almost from the moment he could walk the streets of the Bronx. He grew up quickly and he grew up mean. After his mother’s death, his surviving sister did try to raise him in a cold-water flat on 11th died when Vincent was eleven. He was then taken in by an elderly Irish woman, a neighbour, who treated him like her son.

Run-ins with the law were almost inevitable. Vincent soon developed a reputation for being a wild child of the streets and began the first of several stints in Catholic Reform School before he reached his teens. He was facing a murder charge by nineteen, but that was ‘fixed’ by the crime boss he then worked for. The ability of dirty money to make problems with the law go away was a lesson that Vincent learned early.

Before prohibition, the Irish gangs dominated the Bronx and Manhattan, but during the prohibition era the mobs were increasingly Italian and Jewish and controlled by the likes of Dutch Schultz, the ‘Bootlegger King of the Bronx’ (real name Arthur Flegenheimer), Charlie ‘Lucky’ Luciano, Bugsy Siegel and Louis Lepke. Schultz was the son of a bar-keeper who built up an empire of speakeasies, clandestine alcohol-stills and breweries during the early years of prohibition. In a tough business, with rival gangs constantly trying to carve out their own territory, Schultz needed ruthless, violent young men with a talent for intimidation and killing. Vincent Coll had all of that in spades and started out as an enforcer for Schultz, when he was still in his mid-teens.

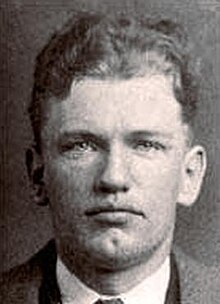

And Early Mugshot of Vincent - While He Was Still in His Teens

By now Vincent and his older brother Peter were beginning to make names for themselves in the Bronx. Vincent was the good-looking one, fresh-faced (some newspaper reports would later call him ‘baby-faced’ or endow him with ‘matinee-idol’ looks), with blond, curly hair, a fondness for sharp suits and an enigmatic, menacing air. He spent small fortunes on his clothes, which were stashed with various girlfriends across Manhattan and the Bronx. He favoured tailored suits, silk shirts, double-breasted Chesterfield overcoats and his signature hat, a pearl-grey fedora, always worn at a rakish angle.

Coll Leaving Court After The Giardelli Case - wearing his trade-mark Pearl Grey Fedora

It was often said of Vincent that he had an ability to appear or disappear at will. He was a lady’s man who always had a girl with a quiet apartment somewhere if he needed to lie low. Coll could be charming or taciturn as the situation demanded and was said to have a magnetic effect on women.

Right from the start of career as a gangster, Coll displayed a maverick, independent streak that would enrage the powerful bosses he was supposed to be working for. Coll was never the classic ‘soldier’. If anything, he was a gun for hire who always had his own angles to work. His real pleasure was kidnapping. And as you would expect from a gangster already known to his associates as ‘The Mad Mick’, he loved a challenge. Coll would kidnap wealthy citizens if the chance arose, but he took an almost perverse pleasure in the insanely risky business of kidnapping fellow gangsters and racketeers.

Two cases illustrate Coll’s love of a challenge. The first concerned Owney ‘The Killer’ Madden: long after his death, NYC Police files revealed that Coll had been paid $35,000 for the safe return of Madden’s business associate George ‘Big Frenchy’ DeMange in the summer of 1931. The money was paid over, but Madden may not have been pleased to see the Irishman then spending some of his money in his own nightclub, The Cotton Club, or parading down Broadway with chorus girls on each arm.

In a second case, Coll demanded another $45,000 to give up George Immerman, brother of Connie Immerman, the famous Harlem night club impresario and racketeer. The Donegal-born gangster must have known that there were easier ways to make a buck than targeting the most dangerous men in New York, along with their families and associates, but right from the start of his career, Vincent had shown zero respect for power or the established pecking order.

As rum-runners working for Dutch Schultz in the mid-twenties, the young Coll brothers were on $150 dollars a week. It was big money for ghetto kids, but Vincent saw their jobs as mere stepping stones. While working for The Dutchman, Vincent set about learning the bootlegging trade and tried to talk some of his fellow bootleggers and enforcers into splitting with Schultz and going into business for themselves (with Vincent in charge, naturally). As part of his scheme, Coll reached out to a Schultz soldier called Vincent Barelli, arranging a meet through his girlfriend, a girl called Mary Smith, who was the sister of a young man called Carmine Smith, a school-friend of the Colls in the Bronx. The meet did not go well. Barelli refused to betray Dutch Schultz so Vincent shot him dead. As Mary Smith was a witness, she got a bullet to the head as well. Vincent then decided it was time to make his move on his boss. In the spring of 1931, he told Schultz, one of the most powerful crime lords in New York, that he wanted a percentage of the business. Schultz refused. ‘I don’t take in nobody as partners with me,’ he was said to have told the young Irishman. ‘You’re an ambitious punk, but you take a salary or nothing. Take it or leave it.’

‘Okay’, said Coll, with his familiar toothy grin, ‘I’m leaving it.’

The result was all-out war. Two Irish brothers, Vincent and Peter, against the King of the Bronx and his army. The Colls went on the rampage, hijacking Schultz’s delivery trucks, shooting his associates and burning out his speakeasies. Schultz could never lay a finger on Vincent; he was just too cunning and too good at hiding himself in the urban jungle. His brother Peter, on the other hand, could be got to. On 30 May 1931, Schultz’s men cornered twenty-four-year-old Peter on a street corner in Harlem and he was killed in a hail of bullets.

Vincent Coll, the Mad Mick, went into a rage of grief and vengeance. Over the next three weeks, he gunned down four of Schultz’s men. In all, around twenty men were killed in the blood-letting; the exact figure is hard to pin down as New York was also in the midst of the vicious Castellammarese War at the same time. It was mayhem on the streets of Manhattan and the police often had difficulty in deciding which corpse belonged to which war.

Coll was seriously out-gunned and tried to even the odds by paying top dollar to freelance hitmen to take out his targets. He raised the money by kidnapping and by trying to muscle in on other rackets, including those run by Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond (an Irishman who started out as Jack Nolan) and Owney ‘The Killer’ Madden. The Irishman was effectively running a protection racket on the racketeers. Even amongst the criminal underworld of New York, Coll was now an outlaw. To be even suspected of running with Coll could bring a death sentence. Dutch Schultz was determined to kill his former employee. In the summer of 1931 he took the highly unusual step of walking into a police station in the Bronx and loudly declaring; ‘I’ll give a house in Westchester to any cop who can kill the Mick’.

On 28 July 1931, Vincent Coll was at the centre of a terrible incident that would see him labelled a ‘Child Killer’ and shock even the war-weary citizens of New York. Coll had tracked down a Schultz associate called Joey Rao and several of his men and went after them on a street in Spanish Harlem as they stood outside a social club tied to Dutch Schultz. Coll opened fire with his Tommy gun while an associate opened up with a pump-action shotgun, but the spray of bullets missed their intended target and instead hit a group of children who were playing in the street. Five children were hit in the crossfire and one, five-year-old Michael Vengalli, died of terrible gunshot wounds to the stomach.

New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker dubbed Coll a ‘Mad Dog’ and a ‘child-killer’ and directed the police to treat him as Public Enemy Number One. Even Vincent Coll realised that he had gone too far. With the police and half the underworld of New York now closing in on him, he hit on a bold strategy. He kidnapped yet another one of Owney Madden’s henchmen and collected a $30,000 ransom. Vincent needed the money to finance his plan and he needed to move fast as there was now a reputed $50,000 bounty on his head. The Irishman had managed to unite the biggest crime figures in New York, Dutch Schultz, Lucky Luciano, Legs Diamond, Owney Madden and Meyer Lansky, in their determination to rub out the Mad Dog. The Mafia, too, had decided that Coll was out of control and making too many waves. Gunning down gangland rivals in the street was one thing. But the violent death of children created the kind of heat that was seriously bad for business.

As the net closed in, Coll broke cover and effectively handed himself over to the police: the New York Times of 5 October 1931 reported the seizure of Coll and his gang at a house in upstate New York as a triumph for fearless detectives, but crime-historians believe that it was Coll himself who was ultimately behind the tip-off that led thirty policemen to his rented hide-out. Coll had grown a moustache and dyed his hair to disguise himself. But the photographs taken shortly after the arrest show him in his trade-mark, pearl-grey fedora. The photos taken at the Bathgate Police station in the Bronx, where Coll was taken to be charged with the murder of five-year-old Michael Vengalli, show a relaxed and well-dressed Coll smiling for the cameras, next to his more dishevelled-looking, but still grinning, associate Frank Giordani.

The Mad Dog could afford to look relaxed even as the entire city bayed for his blood. He had a plan. Coll declared his innocence and used his ransom loot to hire the greatest defence lawyer of the age, Sam Leibowitz, to defend him in court. Coll and his associates were paraded in front of a large crowd of newsmen, gawkers and over two hundred policemen, including New York City Police Commissioner Edward P. Mulrooney and Chief Inspector John J Sullivan, when they were formally charged in the gymnasium at Police Headquarters in the early hours of 5 October.

Vincent wore a pearl grey suit, blue shirt, dark tie, and Chesterfield overcoat with a blue handkerchief poking out of the breast pocket. He confirmed his identity and gave his profession as ‘unemployed brick-layer’. Pretty laughable when the entire city knew who he was and what he did.

Vincent In Court With His Legal Team - There's that Pearl Grey Fedora Again

The New York Times noted the ‘swagger of the young thug’ and reported how he answered all questions related to the murder charges with; ‘I will answer that when I see my counsel’. The charges were put to them by Chief Inspector John J Sullivan, the archetypal New York Irish cop, finally face to face with the most notorious Irish gangster of the era. Inspector Sullivan addressed the prisoners and the crowd, all lit up in the glare of harsh floodlights, through a booming public address system.

‘Coll, there, is a big gangster,’ said Sullivan in what the New York Times reported was ‘a voice with increasing contempt’.

‘He’s a brave fellow, he let a girl claim ownership of the gun found in his room. When I asked him where he got the gun and whose was it, he put it on her. That’s the type of brave young fellow he ‘There’s no doubt about you’re going away, Coll,’ said Inspector Sullivan, turning directly to his fellow Irishman.

‘You’re responsible for killing that child. You’re about as low and despicable as we ever get here.

‘See! (said Sullivan, now addressing the crowd) He’s changed the colour of his hair and plucked his eyebrows and raised a moustache! Oh you boys will go all right. Get out of here!’

The trial of Coll and his associates opened on 16 December 1931 in New York. It should have been a foregone conclusion, but Leibowitz, the brilliant lawyer, had the prosecution on the defensive right from the start. He managed to convince the jury that Coll was actually being framed by the police, the District Attorney and the powerful organised crime figures whom had been deeply embarrassed by the Irishman’s activities. Coll, the alleged child killer, was portrayed as the victim.

When it turned out that the chief prosecution witness was a serial perjurer who virtually made a living from giving evidence on behalf of the police, and had lied about it on the stand, the trial effectively collapsed. Assistant District Attorney James T Neary, the chief prosecutor, was forced to make a motion that the charges by dismissed and Judge Joseph E Corrigan complied. Coll walked out of court a free man on 28 December.

There were also dark rumours about witnesses and jury members being either intimated or bought off, a not unusual practice at the time in the murky world of the New York criminal justice system.

Many policemen and politicians were in the direct pay of the gangsters made immensely rich by prohibition. In 1929, New York Police Commissioner Grover Whalen was paid $35,000 a month by the infamous crime figure Arnold Rothstein, the man who fixed the 1919 Baseball World Series.

So Coll was a free man, but he must have known his days were numbered. He tried to go back to his old rackets, but there was a small army of hitmen on his trail. On 1 February 1932, a team of gunmen burst into an apartment where Coll was said to be staying and killed two of his associates and a woman who happened to be there. Coll himself turned up at the apartment just thirty minutes after the shooting. Seven days later, Coll was in a phone-booth in a drug-store on 23rd at 12.30am when a car drew up outside and one man walked in. Carrying a machine gun, he whispered to the clerk behind the counter, ‘Keep cool, now’, and opened fire on the glass booth.

Some fifteen bullets were taken out of Coll’s body later on at the morgue. He was twenty-three years old. Coll was said to have been on the phone to Owney Madden at the time, threatening to kill him if he didn’t hand over a pile of money.

The Drugstore Where Coll Met His End - Probably at the Hands of Fats McCarthy

One of the only witnesses to the hit was, by coincidence, a Donegal-born woman called Peggy Bonner who had been working at a nearby hotel where Vincent was said to be hiding out.

Coll’s killer was never caught, but the gangland rumour was that the hit had been ordered by his old boss Dutch Schultz and carried out by one of Vincent’s former associates, who went under the name Fats McCarthy. Vincent did leave a wife behind him, a shady woman called Lottie Kreisberger-Coll, herself a killer, serial bigamist and gangster’s moll. Lottie was jailed for her part in a gangland murder two years later. She served her time and disappeared after her release from prison.

Vincent was buried in St Raymond’s cemetery in the Bronx, close to his brother Peter. There were few mourners at the funeral. His family were all dead, his former associates happy to see the back of him. There was one letter of condolence, from Alice Diamond, the widow of his former criminal associate Legs.

In the downtime between his various criminal acts, Coll was said to have talked about someday retiring home to Donegal with his loot, leaving the mean streets of New York far behind him. But few gangsters of the era ever got close to retirement age. And Vincent Coll, for all his mad bravado, must have known that he would never enjoy a peaceful old age.

Hello Mr. O'Shea,

ReplyDeleteI just finished watching an old episode of the Untouchables featuring a Collesque character. Google led me to you. I enjoyed your informative sketch of Mad Dog. Thanks, Curt Anderson, SelectSmart.com

Thanks Curt, glad you enjoyed it - the full story of Coll (and 10 other dangerous guys from history) are in my book, Murder, Mutiny & Mayhem - which is available on Amazon - thanks for reading and commenting!

DeleteHi Joe, great piece on a fascinating and ruthless period in that city's history. Thanks for sharing, I will look for your book. Denis Nestor

ReplyDeleteHi Denis - thanks for commenting and glad you found the story interesting - there's a lot more like that in the book - it's on Amazon and I hope you enjoy it,

ReplyDeleteBest - Joe O'Shea

Riveting...great piece that truly brings the fast paced underworld to life.

ReplyDelete