* He would have been the first Muslim to sit in British Parliament, had he claimed the birthright due to him as an Irish peer of the British realm and a Baron of the County Of Kerry in Ireland.

But Rowland Allanson-Winn was concerned with matters of a higher order than just politics.

Today, there are many questions being asked about the Muslim community in Britain, their place in society, cultural diversity, integration and the shadow of extremism.

The story of Rowland Allanson-Winn points to a different era, when, right back at the start of the 20th century, in what we might consider less progressive times, a pillar of the British establishment could embrace Islam and the Muslim community.

He lived and travelled all over the world - from Killarney to Kashmir. He rejected Christianity and embraced Islam as a religion of tolerance. And his story has long fascinated me......

** (and by the way - if anybody wants to commission a radio or TV doc about this guy, feel free to get in touch and send me money)

Rowland Allanson-Winn

* Rowland Allanson-Winn was a lot of things in his lifetime. A pillar of the British aristocracy & Empire, a boxer, fencer, martial-arts nut, explorer, engineer, author and road-builder.

He also came very close to being crowned the King of Albania (he was offered the throne twice). And was a Baron of the County Kerry in Ireland.

But above all, this son of the British peerage was a Muslim, who choose the name Shaikh Rahmatullah al-Farooq. And he built one of the first mosques in Britain or Ireland, a private prayer space at his ancestral home in Aghadoe, Co Kerry.

|

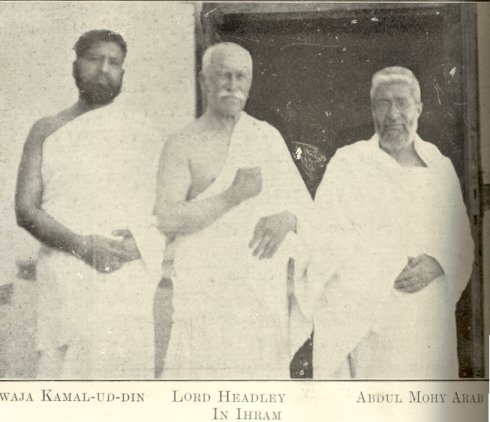

| Allanson-Winn With His Great Friend Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din |

*** Rowland Allanson-Winn was born in London on January 19th, 1855 and was educated at Westminster and Trinity College, Cambridge, in mathematics. After graduation, he had a range of professions, including (for a time) editor of a regional newspaper in Wiltshire.

However, it was in the early 1890s, when he travelled to Kashmir to become an engineer for the British administration in India, that Allanson-Winn first encountered Islam, in the beautiful, mountainous regions of Kashmir.

He was, by all accounts, a fascinating, accomplished and open-minded man. A bit of an eccentric in the best sense of the word. One Irish writer described him as 'a man of many parts, a champion middlewight boxer in his day at Cambridge, a distinguished globe-trotter, an editor and excellent raconteur'.

He was also a keen amatuer boxer and one of the earliest exponents of what we know today as "martial arts". In 1890 he co-wrote one of the earliest manuals about self-defence, the classic "Broad-sword And Singlestick", before going on to write one of the first great books about the art of boxing.

He inherited the title of Baron Of Headly on the death of his cousin in 1913. He could have sat in the House of Lords but did not seek election as an Irish representative. 1913 was also the year that he announced his conversion to Islam, having first encountered the religion in India.

Allanson-Winn had been brought up as a protestant, before studying Roman Catholicism while living in Ireland. But he saw the Christian religions as having what he called a "believe this or be damned" attitude.

He came to know Islam as a religion of tolerance.

“It is,” he said on one occasion, “the intolerance of those professing the Christian religion, which more than anything is responsible for my secession. I was reared in the strict and narrow forms of the Low Church party. Later, I lived in many Roman Catholic countries, including Ireland. The intolerance of one sect of Christians towards other sects holding some different form of the same faith, of which I witnessed many instances, disgusted me. …”

A British Peer announcing that he had converted to Islam today would raise some eyebrows (to say the least). We can only imagine what it must have been like in 1913, when the British empire still held sway over millions of Muslims.

But Allanson-Winn, in his characteristically pugnacious style, made no apologies.

As he said at the time of announcing his conversion (which actually happened in England, after he met Muslims including the Indian lawyer and teacher Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din);

"It is possible that some of my friends may imagine that I have been influenced by Mohammedans; but it is not the case, for my convictions are solely the outcome of many years of thought. My actual conversations with educated Muslims on the subject of religion only commenced a few weeks ago and need I say that I am overjoyed to find that all my theories and conclusions are entirely in accord with Islam? Even my friend Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din has never tried to influence me in the slightest degree. He has been a veritable living concordance, and has patiently explained and translated portions of the Quran which did not appear quite clear to me and in this respect he showed the true spirit of the Muslim missionary, which is never to force or even to persuade.

He would become a chairman of the British Muslim Society, travel and talk in Muslim communities around the world. And he made the Hajj to Mecca in 1923 (see the photo below).

Allanson-Winn, 5th Baron Headley, was a tireless campaigner for the Islamic faith in Britain and abroad and as he lay on his death bed in England in June, 1935, he scribbled a note to his son, asking that he be buried in a Muslim cemetery; “Means permitting I should like to be buried with my brother Khwaja."

It is easy to see him as an eccentric, in the great tradition of the British aristocracy who travelled the world and often became intoxicated by "Oriental mysticism".

But it seems that nobody who met the man in his life doubted his sincere conviction and his belief in tolerance and the values of other belief-systems. He campaigned tirelessly for Muslims and for understanding between the faiths and wrote several books about the Islamic faith, trying to explain its worth to Christians.

The 5th Baron Headly was a bit of a one-off.

***** THANKS FOR READING - THERE ARE SOME NEWSPAPER CUTTINGS ABOUT Baron Headly Below*****

Daily Sketch - 1913

| After a career which has included amateur boxing, civil engineering, the editing of a local newspaper, and expert advice on coast erosion, Lord Headley, an Irish Peer, aged 59, became a convert to Mohammedanism. The conversion was announced at a meeting of the Islamic Society, held at Frascati’s, Oxford street, by the Rev. Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, who is attached to the Mohammedan mosque at Woking. “Those who know me will believe I am perfectly sincere in my belief,” wrote Lord Headley in a letter read at the meeting. Lord Headley may be described as a muscular Mussulman, for when he was at Cambridge he won both the middle-weight and heavy-weight boxing championships. He has written more than one book on the noble art of self-defence. He writes very well, by the way, and has done a good deal of journalistic work in his time. For a couple of years he was editor of the Salisbury Journal. He has also done a lot of civil engineering in recent years. He superintended some coast defence works at Youghal and similar works on the coast to the north of Bray Harbour. He also did some coast defence works at Glenbeigh, his place in one of the wildest parts of Kerry.

A HAPPY CONVERT

The problem of coast erosion has particularly interested him. At Dover in 1899 he read a paper before the British Association on the history of the reclamation of Romney Marsh.Lord Headley is a grey-moustached, handsome man, with a fine intellectual forehead and good features, while his habit of smiling when he talks gives him a happy appearance. |

IRISH PEER TURNS TO ISLAM

That the lure of Eastern religions is affecting an increasing number of Europeans, is again shown by the announcement that Lord Headley, an Irish peer, who spent many years in India, has become a convert to Islam.

The announcement was made by the Rev. Kamal-ud-Din, who is attached to the Mosque at Woking, at a recent meeting of the Islamic Society.

Lord Headley, the fifth baron, succeeded only last January to the title and estates of 16,000 acres in Kerry.

He was born in London in 1855, and has been distinguished as civil engineer, at one time in India and latterly specially engaged in foreshore protection works.

He is an all-round sportsman, being fond of fishing, rowing, skating, swimming, fencing, shooting and golf. In his youth he won the heavy and middle weights as an amateur boxer at Cambridge University.

Lord Headley has four sons, having being married in 1899 to Teresa, youngest daughter of the late Mr. W.H. Johnson, formerly Governor of Leh and Jumoo.

|