* Another pretty long post - but I am fascinated with the repeated attempts by Irish armies to invade Canada and the mad scheme of Yankee Fenians - all veterans of the American Civil War - to free Ireland by capturing Canada, setting up a North American Irish Republic and maybe forcing the US into war against Britain.

It's a bit of a convoluted tale. But it's important to learn its Big Lesson. Which is that Ireland should invade Canada at every given opportunity. And with today's great air-links between the countries - it has never really be easier.

|

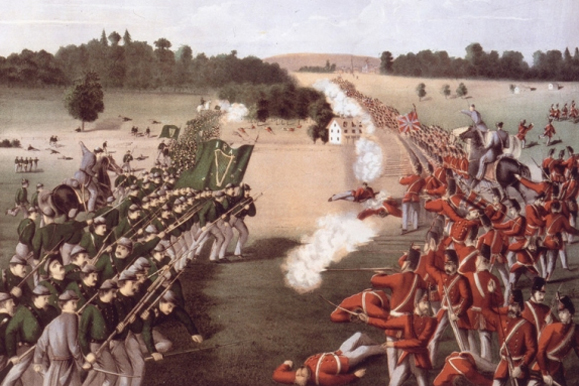

| The Day The Irish Invaded Canada - The Battle of Ridgeway (that's us on the left) |

·

The Book Of Invasions – Or How The Irish

Made Friends & Influenced People. Especially in Canada.

There is one small island, far out on the edge of

Europe, with a proud yet tragic history.

Cursed to be parked next to a powerful

neighbour with a rapacious nature, this island has weathered 800 years of

misery, invasion, colonisation, ethnic-cleansing, another couple of invasions

and – just when things were starting to look up a bit, The Famine.

Always beaten, never defeated. Bloody yet unbowed.

We took the hits and yet, even in the darkest days of the Dark Ages, our saints

and scholars devoted themselves to collecting and saving the wisdom of the

world, eventually setting up a kind of Europe-wide, Monkish mobile library, to

return the light of knowledge to a barbaric continent.

You're welcome, Western Civilisation.

The pagan Irish had

secured the skulls of their defeated enemies to their belts. The Irish monks

who criss-crossed Dark Ages Europe replaced the skulls with bibles and their

precious copies of ancient Greek and Latin texts.

We never asked for thanks, not even as we hunkered

down in our beehive huts on storm-lashed rocks far out on the edge of the known

world, crouched in the candlelight over our fiendishly complicated colouring-books,

awaiting the next invasion, inevitably by a Danish guy called Wulf The

Incredibly Psychotic or, later on, some chinless English toff in a silly hat.

As the great Irish-American politician and scholar,

Daniel Patrick Moynihan so memorably put it; “To be Irish is to know that, in

the end, the world will break your heart..”

Few sentiments have captured the Irish experience

with such maudlin, crying-into-our-pints eloquence. The history of Ireland. It

really would break your heart.

But of course, such lachrymose sentiments only tell half of the

story.

One of the great origin legends of Ireland, the Leabhar

Gabhála or Book Of Invasions, traces

the history of Ireland back to Noah and his daughter Cessair, who is said to

have arrived on our shores forty days before the flood. And it is, as the title

suggests, no heart-warming tale of peace and brotherly love. Put it this way, Disney won't be optioning the rights anytime soon.

The Book is a

strangely familiar story of war, famine, invasion, bloody battles, betrayals, a few more bloody battles, a couple of beheadings and quite a lot of taking of slave girls. Fans of Irish history will also be less

than shocked to find out that there appears to be a hell of a lot of spoofing.

Or as one exasperated Irish antiquarian, who translated the work into English

from the Middle Irish, put it; "There is not a single element of genuine

historical detail, in the strict sense of the word, anywhere in the whole

compilation".

The Book Of Invasions and the oral

histories that came before it really set the tone for Irish history. The ranks

of Saints and Scholars included quite a few Spin-Doctors.

The earliest complete manuscript

which survives dates from the twelfth century, but the original text was almost

certainly composed many centuries before and is essentially the writing down of

ancient Irish sagas. A sort of Old Testament for the Irish, rather than the

Israelites (and just as in the Old Testament, God gets top billing, probably

thanks to some extensive rewrites by early Christian monks with an agenda).

It formed the basis for the history

of Ireland as recorded by medieval scholars and it is, in very simple terms,

the story of one invasion after another. A theme that would be repeated in more

modern times.

Tales of 800 years? We didn’t lick it off the stones.

Of course, we don’t tend to talk about what the

Irish got up to in the wider-world, when the size-12 boot was on the other

foot. Or how we gleefully and profitably joined in with – or even initiated –

some of history’s greatest crimes, from running the Atlantic Slave trade for

the French Kings to doing the heavy lifting on everything from the subjugation

of India to the conquest of Africa.

Ireland can also lay claim to invading (deep breath)

Scotland, the Roman Empire, Canada (five times), Brazil (by accident)*, China, Louisiana

(sub-contract job for the Spanish), Holland, various bits of Germany, France,

Spain, Sweden and Italy and, on more occasions than you might think, England.

In the case of one Irish invasion of England, a

tag-team effort led by Olaf Guthfrithson III, the Norse-Gael King of Dublin and

involving two Scottish Kings, the Irish-Scots invaders were defeated by

Athelstan, King of England, at the Battle of

Brunanburh, in 937.

The location of the battle is now lost in the mists of time

(some believe it was near Liverpool). But although now virtually forgotten, Brunanburgh

has been called, by one leading medieval historian, “the moment when

Englishness came of age”. So we can take the blame for that, too.

It’s true, that in many cases, these invasions were

on an ad-hoc or freelance basis, either by Irish warlords operating on a

smash-and-grab basis or entire regiments of Irishmen (and generals) in the pay

of Foreign Kings.

But it was not all so very long ago. At the start of

the 1840s, Limerick man Sir Hugh Gough was the Commander-in-Chief of the

British forces in the First Opium War, a large-scale invasion of the Empire of

China, to force the Chinese to allow countless thousands of tonnes of Bengal

Opium to be sold by the British into their country.

It was the drug trade on a

globalised scale. Sanctioned by the British Government, who were tired of

seeing their gold and silver reserves flow East to pay for tea, silks and

porcelain. Gough’s army included thousands of Irish soldiers then serving in

India, including The Royal Irish Regiment.

They smashed their way into the

southern ports of the Heavenly Middle Kingdom and forced the abject surrender

of the Emperor’s forces. What followed was widespread addiction to opium (the

number of Chinese addicts may have been as high as 10 million in the aftermath

of the war) and terminal decline, a “Century Of Humiliation” for the Chinese.

The Limerick Opium Warlord also bagged Hong Kong as a bonus prize.

In the case of the Irish invasion of Canada in 1866,

the Irish aggressors didn’t even have the excuse of acting under orders from

the British.

Several large Irish armies, almost 25,000 men, most

of whom had just fought on both sides of the American Civil War, claimed to

represent an Irish Republic and marched under the Green Flag.

· When The Irish Invaded Canada

Viewed from today’s stand-point, the multiple

attempts by Irish Republican forces to invade Canada now looks part

comic-opera, part mad scheme.

But the men behind it were deadly serious, and some

historians believe their plan had at least some grounding in reality and some

chance of causing major problems from the British (and the Americans).

|

| See! I'm Not Making This Stuff Up. |

Over a decade during the famine years, from the

mid-1840s on, more than one million Irish emigrated to America. Many thousands

of them ended up fighting in the

American Civil War, mostly on the Union side

but also entire regiments for the Confederacy (it is estimated that around

150,000 Irish-born soldiers fought for the North, 25,000 for the South).

The Irish were on every battlefield, on a number of

occasions facing each other, such as at the terrible slaughter at the Battle of

Antietam, the “Deadliest Day”, when over 23,000 soldiers were listed as killed,

missing or wounded during 12 hours of slaughter outside the town of Sharpsburg,

Maryland on September 17th, 1862.

The Irish Brigade of the Union Army reported 50 per

cent casualties. As did the mostly Irish 6th Louisiana, their

countrymen on the other side.

When the war was over, there were thousands of

battle-hardened Irish soldiers, most of whom had a bitter enmity for the

English, offering a ripe recruitment ground for the American branch of the

Fenian or Irish Republican Brotherhood movement.

Originally established to raise funds and source

weapons to be sent across the Atlantic for rebellion against the English, the

newly energised American Fenians decided on a new, more pro-active strategy. Thinking

outside the box, they would take the fight for Irish freedom north to British

Canada. They would either establish an Irish North American Republic on

captured land or hold Canadian provinces ransom for the freedom of Ireland.

In 1865, an American ship, the Erin’s Hope, was intercepted by the British navy en route to

Ireland. The ship was loaded with men and ammunition bound for a planned Fenian

revolt. When this mission failed, the American Fenians resolved to hold an

emergency convention in Philadelphia.

A man called William Randall Roberts, something of a

firebrand, was elected president and he pushed a new, secret plan for action

for the Fenians, the invasion of Canada.

Even to the most radical American Fenian, it might

have seemed like a foolhardy plan.

They would risk open battle with British

troops and turning the American government and public against their cause.

But the Irish Nationalists in America were at

something of a high-water mark. They had widespread support for their cause,

thousands of trained men and weapons (bought cheaply at the end of the Civil

War). Canada’s borders were virtually open, protected only by a weak citizen

militia and some scattered British regular troops.

They also had the blind eye, at the very least, of the

US Government, which had recently had very difficult relations with the British

Crown. The Union Government was outraged at the British conduct towards the

Confederate Rebels, British merchants had continued to buy Southern Cotton and

sell arms and supplies to the Rebs, even as Washington had Confederate Armies

at the gates. The US Government was also looking for millions of dollars in

reparations for Union ships sunk by the British navy during the war. A Fenian

invasion of Canada might concentrate the minds of the British.

If the Fenians could strike fast and secure strategic

towns and transport hubs, they could block reinforcements, secure the support

of the 175,000 Irish who had emigrated to British Canada during the recent

Great Hunger and possibly even exploit the tensions between the French

Canadians and their Anglo-Canadian neighbours.

A successful invasion of Canada by Irish forces might

draw off British troops and allow an uprising in Ireland, or even spark a war

between the USA and the British Empire, who had already been at war just five

decades previously in the War of 1812 and had come very close to resuming

hostilities during the Civil War.

The initial plan was audacious, some 25,000 Irishmen

would invade Canada from three points, with the initial aim of capturing Quebec

and making it the seat of an Irish Republic-In-Exile. The Irish army would march

under a Green White And Orange tricolour and wear green uniforms, with buttons

engraved with the letters “I.R.A” for Irish Republican Army, the first time

this designation was made.

|

| It Was Supposed To Go Like This |

And as well as Irish-Americans, the forces would

include 500 Mohawk Indians, who had been fighting the British along the border

since the early 1700s and a company of 100 black veterans of the Union Army who

were sympathetic to the Irish cause.

A western force of around 3,000 men was to assemble in

Milwaukee and Chicago, under the leadership of Civil War veteran Brigadier-General

Charles Tevis, a West Point graduate and adventurer who had a thing for travel

and mad military escapades, later serving with armies in Turkey, Egypt, Bulgaria

and France.

The central force of 5,000 men was directed to gather

in Cleveland, Ohio under under General John O’Neill, a colonel in the Union

army and native of Drumgallon, County Monaghan who would go on to personally

invade Canada three times, in 1866, 1870 and 1871.

O’Neill and Tevis were meant to be distractions. The

main force of Fenians, some 16,800 Irish Civil War veterans under

Brigadier-General Samuel M. Spear, a cavalry man and veteran of wars against

the Indians and the Mexicans.

After the two smaller Irish armies had gone in,

General Spear was to lead his regiments from St Albans, Vermont, over the

border and strike at Montreal, as the British would already have moved whatever

forces they had to counter the earlier incursions.

This being an Irish plan, secrecy was not high up on

the agenda. Newspapers in border towns like Buffalo had been full of letters

and opinion pieces calling for action on behalf of Old Erin. One prominent

Fenian, Patrick O’Day wrote to his local newspaper in upstate New York to

helpfully explain; “The plans for action are perfected, and all that is now

required is arms to place in the hands of the thousands of brave men who are

today ready to take the field and fight for their country’s liberation”. O’Day,

an auctioneer in Buffalo, must have assumed British agents wouldn’t read the

newspapers.

Many of the Irishmen recruited to fight had been made

a promise, a bounty of 100 pounds and 100 acres of Prime Canadian farmland once

the Irish Republic of North America had been established.

And as they began to assemble on the border and

rumours started to fly of a Fenian invasion, nerves started jangling on the

other side of the border. There were rumours of blood-thirsty Irish militias

ready to descend on peaceable Canadian farms, bringing death, destruction and,

even worse, their Papist Priests with them. Priests were actually said to be

using Mass services to recruit Irishmen for the force.

In taverns on both sides of the North East border

between the USA and Canada a new ballad began to be sung;

We are the Fenian Brotherhood,

skilled in the arts of war,

We’re going to fight for Ireland, the land we adore,

Many battles we have won, along with the boys in blue,

And we’ll go and capture Canada,

Sure we’ve nothing else to do

We’re going to fight for Ireland, the land we adore,

Many battles we have won, along with the boys in blue,

And we’ll go and capture Canada,

Sure we’ve nothing else to do

In the early months of 1866,

British agents were watching nervously as Irishmen began to move north to the

border in numbers from all over the USA.

In May, one alarmed British

intelligence officer sent an urgent cable to his bosses on the other side of

the border, which warned that there were “many strange military men” in Buffalo, New York. He followed that up

with a more alarming telegraphed message within 24 hours, which baldly stated; “This

town is full of Fenians!”.

However, the numbers of

Irish Civil War veterans envisaged under the plan failed to materialise. When

General O’Neill turned up in Buffalo at the end of May, he had one-fifth of the

5,000 troops promised. The Irish forces did have canal boats to transport them

across the Niagara River to the vicinity of Fort Erie, Canada (an initial

target).

But the elaborate plans

laid down by the Fenian leadership were beginning to unravel.

As confusion and counter-orders began to spread,

O’Neill decided that any further delay could be fatal and in the early hours of

June 1st, one thousand Irishmen crossed the Niagara River to land in

Canada.

On landing, instead of pushing westwards to attack the

nearest military posts, O’Neil set up a defensive position and waited. One

detachment did press on to Fort Erie and managed to capture six men of the

Royal Canadian Rifles. The commander of this small force, perhaps knowing his

men, immediately posted sentries at the doors of the local taverns and ran up

the Irish tricolour over the old and mostly abandoned fort.

The few startled locals were then addressed by the

Irish commander, Colonel Owen Starr, who read out a proclamation stating;

“We come among you as the foes of British rule in

Ireland. We have taken up the sword to strike down the oppressor’s rod to

deliver Ireland from the tyrant, the despoiler, the robber … We have no issue

with the people of these provinces, and wish to have none but the most friendly

relations. Our weapons are for the oppressors of Ireland. Our blows shall be

directed only against the powers of England; her privileges alone shall we

invade, not yours.”

The small Irish contingent then seized some food and

drink (promising to pay the locals from the funds of the provisional Irish

Republic, once it was established) and settled in to wait.

The American government, the Union men who had been

close to conflict with Britain for her merchants’ support of the Confederate

Armies, was very nervous when the news came through and troops and ships were

mobilised along the border as tensions rose.

Back in Buffalo, additional Fenian reinforcements were

gathering. However, the American government, which had largely given the

Fenians free rein in the past, found itself in a precarious position. With

tensions between the U.S. and England still high due to England’s support of

the Confederacy during the Civil War, the Fenian invasion could be a lit match

tossed upon a powder keg, seen as an American act of war.

O’Neill finally decided to move the Irish forces to a

new position later on the first day and they finally encountered the British

forces at a piece of high ground known as Ridgeway.

The British forces had expected to run into a bunch of

drunks and blaggards, what they actually met was a well-disciplined, well-led

force of veterans. When the two sides clashed at Ridgeway, volleys of gunfire

were exchanged and after some initial success against Irish scouts, the British

pushed forward only to run into an ambush.

After more heavy gunfire and widespread confusion, the

British forces withdrew, chased by the Irish.

Some twenty eight men were killed (10 British, 18

Fenians), 62 men were wounded (38 British, 24 Fenian) and the Irish held the

field. The battle at Ridgeway would prove to be the high-water mark for the

Fenians. It was also a rare, if relatively small, success for Irish forces in

open battle against regular British troops.

After a second victory against a small contingent of

British troops being rushed into the area by canal boat, O’Neill, the Irish

Fenian commander, decided to fall back on Fort Erie and wait for news of the

other two Irish contingents to the West.

He soon learned that Tevis and Spears had not even

gotten off the start line. His group of 1,000 Irish Fenians were the only ones

to cross into Canada. Other Irish reinforcements could not find transport

across the Niagara.

Realising that the game was now up, O’Neill pulled his

forces back to Buffalo the following morning.

The Irish forces were intercepted by the US army and

held in open boats for three days while the men in Washington decided what to

do with them.

O’Neill and his men were charged with violating the

Neutrality Act of the United States. But there was little appetite for throwing

the full weight of the law against the Union Army Veterans who had carried the

Stars and Stripes through the hells of Antietam, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg.

The rank and file were released after a few days and

given tickets to return home to the native states. In return, they were sworn

to renounce their Fenian oaths and give their word not to invade Canada again.

Once the immediate furore had down and life along the

border began to return to some sort of normality, O’Neill and his officers were

quietly paroled and told to get the hell out of the border country.

The British, who were not satisfied and pressured US

President Andrew Jackson into making a statement which underlined his intention

to strictly enforce the Neutrality Act and respect the Canadian border. Jackson

also ordered the arrest of leading Fenians.

The subsequent arrests, infighting and blame fatally

weakened the Fenian movement. There were several other attempts to “invade”

Canada by various bands of disaffected Irishmen over the next three years but

they came to nothing other than some skirmishes, arrests and deportations.

|

| A Young Fenian Soldier Lies Dead on The Road Near Eccles Hill - Rare Photograph of the Fenian Raids |

The Battle of Ridgeway became a historical footnote.

But in a strange way it did change Canada. Realising that their border was

largely undefended and unwilling to trust the British to do the job, Canadians

put an even greater urgency into their push for Confederacy and greater control

of their own destiny. The Federal Dominion of Canada was established 13 months

later to the day of the Irish invasion, on July 1st, 1867. It also

strengthened the British colonial hold on Canada.

On June 6, President Andrew Johnson, bowing to

pressure from the British, issued a statement reinforcing U.S. neutrality and

calling for the arrest of the leading Fenians, including Fenian President

William Randall Roberts.

This proved to be the death knell for the Fenian

movement in America. It proved that the U.S. government would not support an

Irish rebellion, despite the growing political influence of the Irish. The

invasion accelerated the Canadian push for Confederation, as the Fenians had

shown that Canada’s defenses were unsatisfactory. The Fenians attempted

additional invasions into Canada, but each attempt fizzled, and the Fenian

cause

generally fell out of favour in America.

generally fell out of favour in America.

Today largely forgotten, the Irish invasion of Canada

and the Battle of Ridgeway is one of curious footnotes that jars with the

Official History of the Irish in North America.

If the operation had been better organised, if the

Irish republican forces had managed to seize Quebec, bring the numerous and

dissatisfied French and Irish Canadians over to their side and force a conflict

between the US and Britain, history on both sides of the Atlantic might now

read very differently.

ENDS - Thanks for Reading.

Great stuff Joe. As usual with Irish History, the word 'nearly' springs to mind !

ReplyDeleteThanks! Coulda, shoulda, woulda - it's our history.

ReplyDelete