* This Saturday in London, a group of protesters intend to march to the HQ of broadcasters Channel 4 to voice their anger over a proposed sit-com - set around the Irish famine.

The march is being organised by the Campaign for the Rights and Actions of Irish Communities - the rather ironically acronymed CRAIC.

The protest was organised before the Charlie Hebdo outrage in Paris. And it may seem crass to draw comparisons. But you might think it's a little strange that as the world shouts for freedom of expression and artistic licence to take on even the most controversial subjects and issues, a fair proportion of Irish people are vehemently opposed to a comedy script that hasn't even been fully written yet.

It's not as if humorists haven't worked with subjects like millions of starving Irish people or the holocaust before.

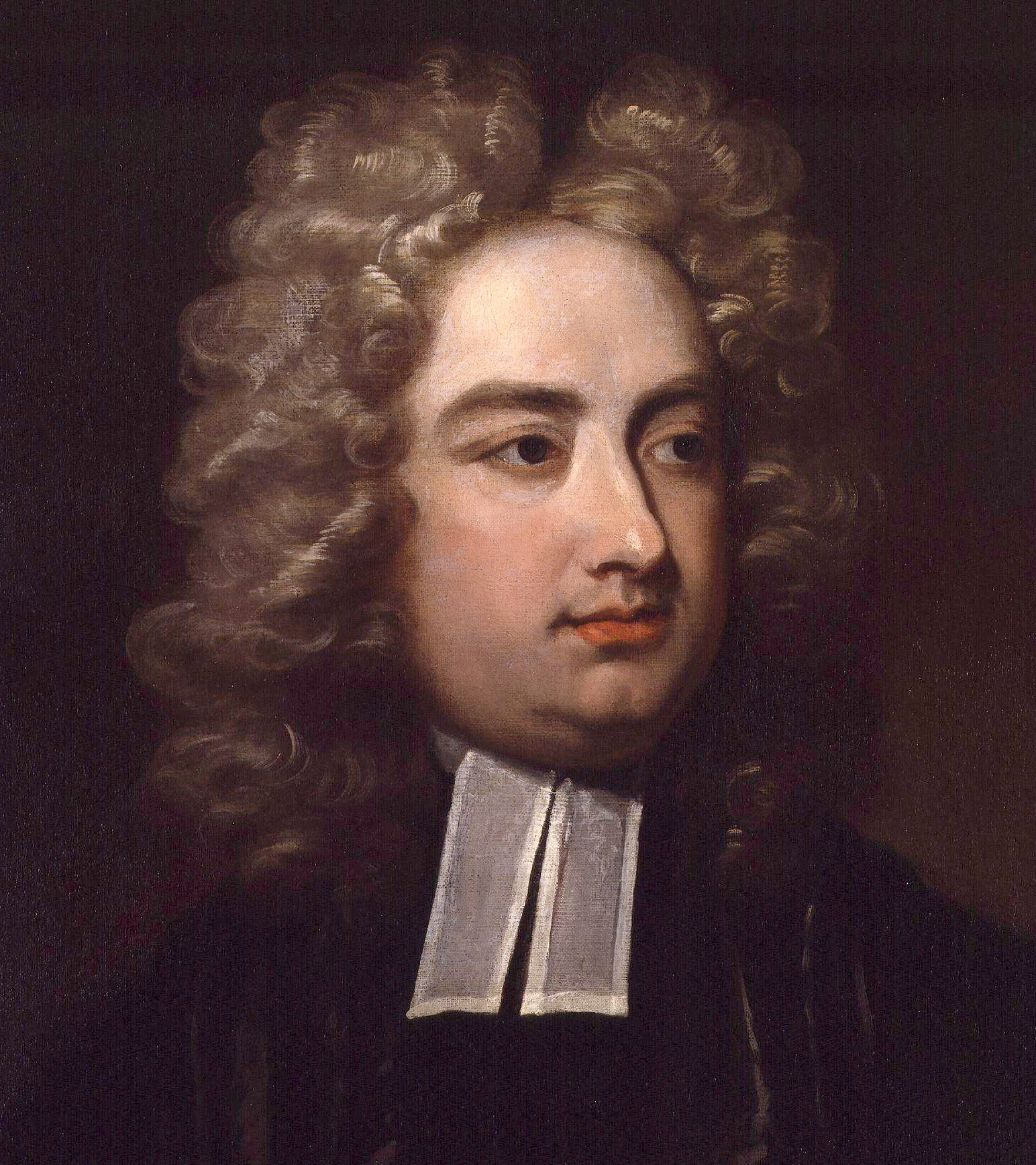

Irish satirist Jonathan Swift once made a “modest proposal” that the starving Irish could ease the burden by selling their children as food for rich Lords and Ladies. He was joking, of course.

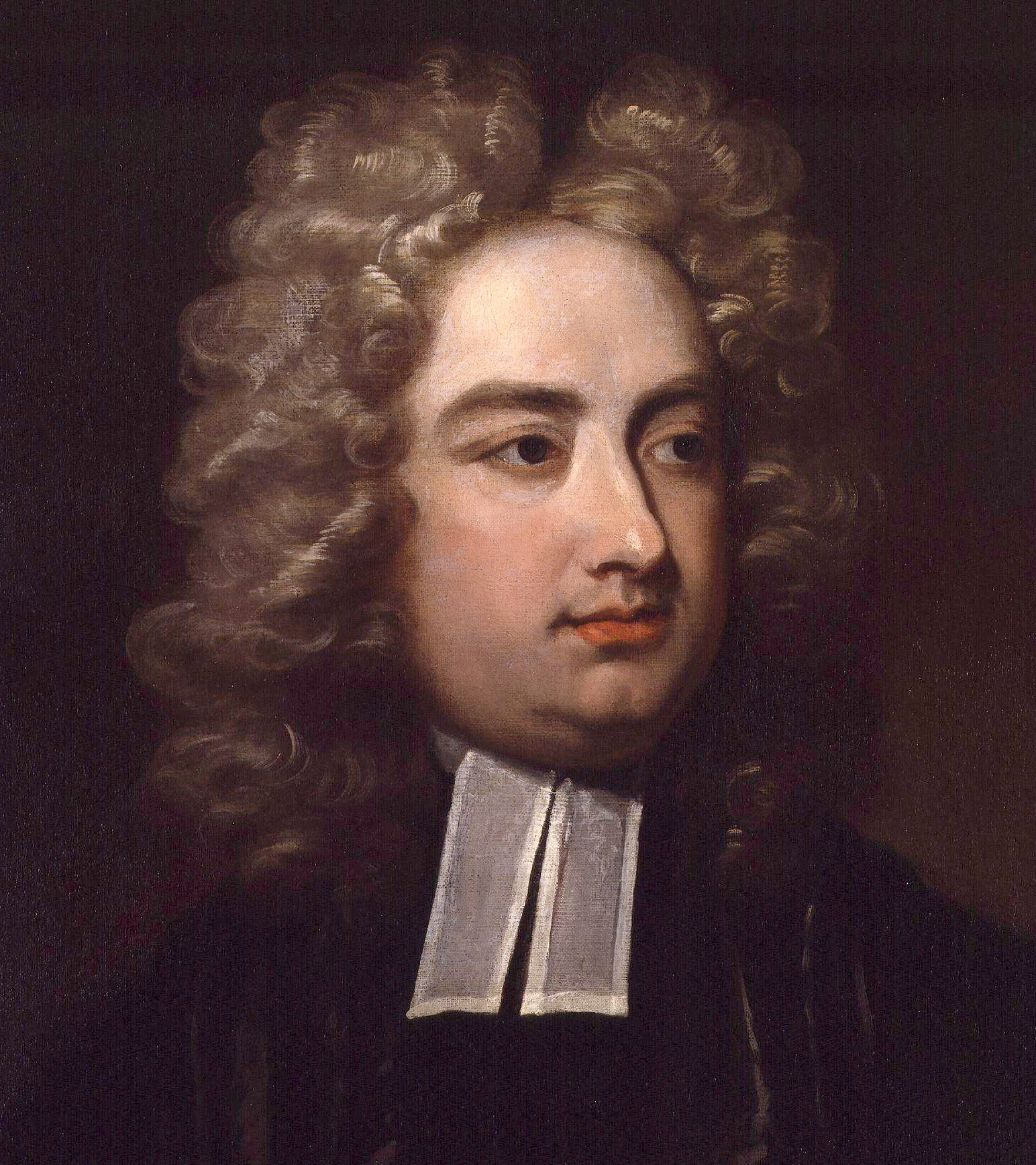

|

| Auld Swifty - He Also Did Fart Jokes |

Jewish comedians such as Mel Brooks, Charlie Chaplin and Joan Rivers satirised the Nazis. And the late Rivers got into serious trouble in 2013 by observing of the German supermodel Heidi Klum; “The last time a German looked this hot was when they were pushing Jews into the ovens.”

Answering the outrage generated by her Holocaust joke, Rivers said: “My husband lost the majority of his family at Auschwitz, and I can assure you that I have always made it a point to remind people of the Holocaust through humour.”

|

| Der Furher Was A Wunnerful Dancer! |

Monty Python were accused of sacrilege because of “The Life Of Brian” while the Blackadder team mined comedy gold from the horror of WWI trenches.

Comedians and satirists have always played with fire when it comes to grim historical events. But it could be argued that the best, like Swift, have used humour as a weapon against evil. As well as making us laugh.

Anyhow! I talked to Irish comedian, satirist and impressionist Mario Rosenstock, and Professor Gary Murphy about this, ahem, hot potato.

|

| Knowing Me, Knowing Potato Blight |

* The Great Famine! It’s no laughing matter. Unless you

are Channel 4 or Alan Partridge.

In one classic, 1997 episode of the BBC comedy I’m Alan Partridge, the hapless TV

presenter sat down with two Irish TV executives, played by Fr Ted writers Arthur Mathews and Graham Linehan.

Alan blundered into the subject of the Famine, asking

a clearly uncomfortable Linehan (playing TV exec Aidan Walsh); “So, how many

people were killed in the Irish famine?”

The Irishman replies; “Two million. And another two

million had to leave the country”.

Patridge observes; “Right. It was just the potatoes

that were affected? At the end of the day, you will pay the price if you are a

fussy eater. If they could afford to emigrate, then they could afford to eat in

a modest restaurant”.

If you thought that joke was in desperately poor

taste, you may be one of many thousands who signed an online petition this week

to demand that Channel 4 drops tentative plans for a sitcom set during the

Famine.

Irish comedy writer Hugh Travers has been commissioned

by the British broadcaster to write a pilot script for a “black comedy”,

working title Hunger, set during the

period around Black ’47.

It is to be produced by Deadpan Pictures, a spin-off

of the Wicklow-based production company Grand Pictures, the people behind hit

comedy Moone Boy.

“This

is in the development process and is not currently planned to air,” said a C4

spokeswoman. “It’s not unusual for sitcoms to exist against backdrops that are

full of adversity and hardship.”

Hugh

Travers, best known for the RTE radio comedy-drama Lambo (a fictionalised account of the moment the late Gerry Ryan

confessed to killing a lamb on The Late Late Show) told one newspaper about his

thought process.

“Why

the famine? Well, they say ‘comedy equals tragedy plus time’. I don’t want to

do anything that denies the suffering that people went through, but Ireland has

always been good at black humour”.

Travers

may be shocked by the furore generated by his development script.

But

another Irish comedian and comedy writer, Mario Rosentock, believes one factor in

the outrage generated is social-media in general and Twitter in particular.

“Quite

clearly, people are only too ready to jump on the outrage bandwagon,” says

Mario.

“They

can use this 140-character outlet to make a name for themselves, to get

noticed. Twitter is like going into a bar and shouting at the top of your voice

until everybody shuts up. And the best way to do this is to be rude or outraged

about somebody, some TV show or whatever”.

|

| Mario Rosenstock as Himself |

The

radio and TV comic says he wants to wait and see how the script turns out but

he does not believe that the Famine should be off-limits for comedy.

“With

a subject like the famine, the tone is going to be very important, it’s the

overriding factor in any comedy like this,” says Mario.

“You

look at shows like Blackadder, set in the horror of World War One, and they got

it right, even up to that ending, where they went over the top, and suddenly

it’s very powerful, it’s not about comedy anymore”.

“And

just who is doing the jokes is also a very important factor. It kind comes back

to the debate about how black comedians can use the N-word, but white comedians

cannot.

“It’s

largely because they are saying it about themselves.

“The

fact that it’s an Irish writer, an Irish production company, and not English

writers and producers doing this, I think that allows them, if that’s the right

word, to at least look at the subject.

“In

this case, the receivers of the injustice, some people would argue the genocide,

are the ones who are writing something funny about it, or attempting to see the

funny side of it.”

DCU

Professor of Politics Gary Murphy believes that, on a basic level, no area of

Irish (or wider) history should be off-limits for satire or comedy.

“It’s

part of the human condition. We have been through all sorts of trauma, from

famine times, a bitter, terrible civil war, right up through the troubles.

“And

if we can’t occasionally make fun of our history, this human condition, well

what’s the point of it all, really?”

“It’s

also a dangerous road to go down. Once you start putting events off-limits,

where do you stop? Do you not lampoon the Troubles, or the War of

Independence?”

“It’s

our story. And if comedy should do anything, it should enlighten that story.

These terrible events should be up for discussion in all forms. And comedy is

as much a form of political expression as any other”.

Professor

Murphy believes some of the negative reaction to the Channel 4 project comes

from professional historians and commentators.

“We

can get too po-faced about our history, saying we can only talk about these

events in dry history books or serious commentary. It inhibits free speech and

imagination.”

The

academic believes that we may also be doing a disservice to the people who

actually lived and suffered through the famine.

“We

can only assume that people then had a sense of humour, not withstanding the

unbelievably grim conditions, that’s just part of the human condition. And this

idea that only historians can feel their pain, or because it was so terrible -

and you can make the strong argument that the British Government just let the

Irish to rot - that we can only talk about it in the most serious tones, well I

find that very limiting.”

But

should any subjects be off-limits for comedians? Mario Rosenstock says it’s an

issue that he wrestles with and gives the example of Scottish stand-up Frankie

Boyle’s notorious routine about the disabled son of glamour model Jordan.

“I

don’t understand how Frankie Boyle, a man of his intelligence, needs to make

jokes about Jordan’s disabled son. Yes, what he is doing there is showing us

that he can do it, that it’s freedom of speech.

“But

you can’t honestly say it’s funny. Nobody with a heart can say it’s funny. As a

sentient human being you can’t go and laugh at that”.

******Hey! Thanks for reading!******