This piece is about Ms Du Plantier, but also about this wild, beautiful part of my home county, a part of Cork which I know very well, having spent every summer there as a kid and teenager, and still making regular visits back. Many of my own happiest memories revolve around Crookhaven, Barleycove, Schull & environs. I think it's one of the most beautiful places in the world. But it has an often dark history - it was almost always desperately poor & isloated, it was was one of the worst hit regions in the Famine - and can be a strange, lonely place in the winter, when the Atlantic storms (or worse, endless days of mist and rain) batter or smother the rolling rocky hills, mountains and coastline....

|

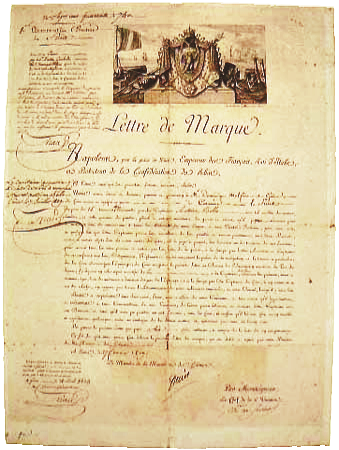

| Toormore is between Schull & Goleen - Bottom of the Map |

|

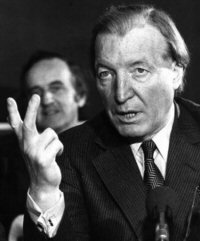

| Sophie Toscan du Plantier |

Talk to the French who have colonised West Cork and they will rhapsodise about its beauté sauvage.

Sophie Toscan du Plantier loved, more than most, that sense of being where the wild things are.

The sophisticated Parisienne often travelled to her isolated farmhouse on the Mizen peninsula in deep winter, when almost all of the affluent French, German and British blow-ins who summer around Schull, Bantry and Glandore were long gone.

West Cork, glorious and vibrant when the sun shines and the yachts are in, is a different country in the winter.

Conditions vary between furious coastal gales and days of thick sea fog and hill mists that suck any sound and light from the landscape.

The glacier-gouged, gorse-scrub landscape, so benign in high summer, can be sinister and claustrophobic as the days shorten.

The harsh landscape is reflected in West Cork folklore, chilling ghost stories and supernatural tales of banshees and menacing fairy folk who abduct unsuspecting travellers in the night.

I remember being in a farmhouse as child, on the Northside of the Mizen in 1979. The homes on this exposed side of the furthest point south in Ireland had only just been connected to the electricity grid. Some were still using kerosene lamps to light their kitchens at night. This was in 1979, as Apple Computers were building their first European manufacturing plant in Cork city - two hours drive away.

In that same summer, we cowered in our caravan in the sand-dunes as a furious Atlantic storm hit the annual Fastnet yacht race, just offshore, killing 18 people, 15 sailors and three rescuers. The next morning, we walked up to Crookhaven and saw some of the battered yachts being towed in by fishing-boats.

It is not so long ago. And while new roads and hotels have changed West Cork in the past two decades or so, it the winter, it still feels like a very isolated place.

Once the tourists are gone, many houses are deserted and most of the shops, pubs and restaurants put up the shutters and hang out their faux-cheery "Closed for the Season - See You Next Summer!" signs.

When Sophie flew into Cork, alone, on December 20th 1996, she would have seen the lights go out, one-by-one, as she drove west through Bandon, Clonakilty, Ballydehob and Schull.

By the time she reached the isolated townland of Toormore and turned into the dark, twisting boreen that lead to house in an small valley, she would have felt very alone.

The lights were on in the rustic kitchen, solitary pricks of light in the all enveloping darkness.

Sophie's housekeeper, Josephine Hellen, had lit a fire in the old fashioned grate and placed freshly picked holly, with bright red berries, on the windowsills to give the house a more welcoming, Christmassy feel for the lady travelling alone through the dark.

The night before, the 39-year-old film producer had enjoyed drinks with friends and her husband in chic Paris nightclub Les Bains Doucheson the Rue Bourg-L'Abbé.

Less than 24 hours later, the only light visible from the rocky hillside overlooking Roaring Water Bay was the thin finger probing through the sea mist from the lighthouse on the Fastnet Rock, eleven kilometres out to sea.

Her friends say Sophie loved the light from the Fastnet, she had her bed in the farmhouse's master bedroom specially raised so that she could see watch the narrow beam as it swept across the headlands every five seconds.

The interior of the house is as you would expect from a French woman who loved the idea of having an old Irish farmhouse, antique dressers, side tables and reed-woven stools.

When I returned to this area to write about it several summers ago, Toormore, with its nearby sandy beaches and rocky inlets, was bathed in spring sunshine and the white farmhouse stood out against the green hillsides in a little valley.

But as dusk fell, you got a sense of just how isolated the farmhouse was

Neighbouring holiday homes are often empty and the only light that was visible from the valley is the far off Fastnet lighthouse.

It is a lonely place, far from the main road that skirts the coastline and deadly quiet and dark after sunset.

When Sophie went there in the winter of '96, she travelled to the farmhouse alone, having tried but failed to persuade a couple of close friends to join her for a short Christmas break.

Sophie was not alone over the next 48 hours, she visited close friends and enjoyed a quiet sandwich and a cup of tea in the harbour village of Crookhaven.

But she was by herself when an unknown assailant called to her home in the early hours of Monday, December 23rd.

Her battered body was found, by a neighbour, close to the gate at the bottom of the road leading to her house shortly before ten am on that morning.

She had been dressed as if called from her bed in the early hours of the morning, her torn and bloodied dressing gown was found close to the body, there were bloodstains on the gate as if she had tried to scramble over it during the assault.

Sophie's mother Marguerite told staff at Cork University Hospital that she could only identify her daughter by the distinctive shape of her nose, the only part of her face still intact after the brutal attack.

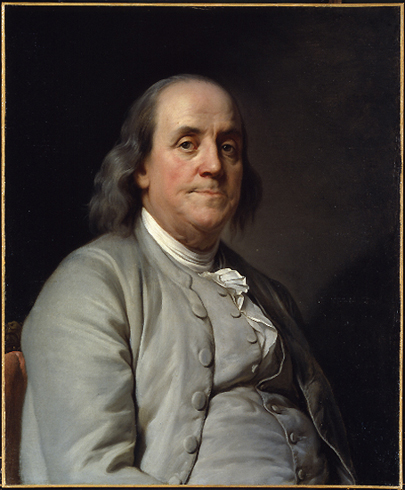

|

| Sophie's Parents at the home in Toormore - Pic Irish Examiner |

When I visited some 13 years on from that winter night, Sophie's family had just taken the latest dramatic step in what has been a tortuous journey towards justice.

Iain Bailey, who has been arrested and questioned twice by gardai in relation to the murder but proclaims his total innocence, was facing an extradition request from Paris-based magistrate, Patrick Gachon.

Gachon was appointed in 2008 ago to carry out an investigation into the murder after a long campaign by Sophie's family that included representations to the French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

The extradition, as we now know, would not happen.

The white farmhouse in Toormore is today owned by Sophie's son from her first marriage, Pierre-Louis Bauday.

Soft spoken and polite, Mr Bauday told me in 2010 that the house that so entranced his mother is still a special place for him and remains unchanged from when Sophie was alive.

He still travelled to the West Cork home every summer and when he goes, he passes the spot where his mother died, he sees the small Celtic Cross memorial with the single inscription, "Sophie".

"It was where I stayed with my mother, it has not changed, it is still intact and I prefer to keep it private," said Mr Bauday.

"I still go there, I will travel there in the summer, it is a beautiful place."

Publican Dermot O'Sullivan, who runs the family bar in Crookhaven, was one of the last people to see Sophie alive when she called into the pub on the pier on Sunday 22nd .

Dermot, who speaks French, had chatted with her as he did with most of the French customers who flock to the pub that Sophie loved for its famous seafood and views over Crookhaven harbour.

"We always chatted about the weather and the usual stuff, I got the sense that she was a very private person," said Dermot.

"I think she loved the peace and tranquillity that you get down here and I think she liked the lack of intrusion into her life."

"A lot of the Europeans who come here are looking for that, they tend to live pretty quietly, I suppose it's what they are looking for if they come from a big city."

"We are very busy in the Summer but it can feel isolated in the winter, especially when the weather is bad. But some people are looking for that."

Dermot said Ms du Plantier's death has left a "bit of a shadow" over the area, mostly because of the ongoing pain felt by her family who have yet to see justice done.

West Cork people, possibly because of their isolation, are famously hospitable and feel protective towards those who visit their townlands.

In the summer of 1996, months before the murder, West Cork was being written up in the British press as "the new Dordogne", an Atlantic seaboard colony for discerning celebrities, media industry figures, artists and taste-makers.

The London Independent newspaper and several glossy magazines ran features pointing out how it was now the second-home destination for everybody from Jeremy Paxman and Jeremy Irons to Sir David Puttnam and Edward de Bono. Chatshow host Graham Norton, himself from Bandon at the gateway to West Cork, now has a holiday home near Ahakista, about a half hour drive from Toormore and close to the Sheep's Head peninsula.

The word from the Independent back in the mid-90s was that "the attractions of Sarlat and San Gimignano have paled besides those of Ballydehob and Skibbereen".

The terrible murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier did not stop the influx of affluent, often powerful people looking for an idyllic, largely unspoilt home.

The stylishly renovated farmhouses and Victorian ex-parsonages and country homes that are hidden away down winding boreens or behind high walls still command big money, that's when they come to the market at all.

But the ghost of Sophie Toscan du Plantier still lingers, a spectral reminder that the savage Atlantic coastline can be baleful as well as beautiful.

ENDS