* Did you know that an army of our forefathers went out to Brazil many years ago. And had a crazy time in the old Ciudad Maravillosa. In fact, they burnt it to the ground.

You may be surprised to learn that Brazil once had an emperor - and even more surprised to learn that the most dangerous forces he ever faced were 2,500 blood-thirsty farmers from Cork and Waterford - in the Irish province known as Munster - and an Irish Admiral who took, sank or destroyed his Imperial Navy........

I thought I would tell their long-forgotten story.....

|

| Emperor Dom Pedro I - No Friend Of The Irish - The Fecker |

We don’t know much about Colonel William Cotter, beyond the fact that he was a con-man, a killer and a right bad bastard.

In the early nineteenth century, Col. Cotter managed to trick more than two and a half thousand Cork and Waterford farmers into leaving their homes and crossing the broad Atlantic to fight for the Emperor of Brazil.

In one of the more bizarre episodes in Irish history, Cotter, an Irish soldier of fortune in the service of Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil, was responsible for luring the Irish men, women and children to South America with the promise of a new life. When they arrived, they discovered that, far from farming, they were to form an ‘Irish Legion’ to fight against Argentinean-backed rebels in the war of the ‘Banda Oriental’ in present-day Uruguay.

In the end, the only fighting most of them saw was with German immigrants, African slaves and Imperial soldiers on the streets of Rio de Janeiro. The Irish-led rioting in the hot summer of 1828 left hundreds dead and a large part of Brazil’s Cidade Maravilhosa – marvellous city – a smoking ruin; their murderous rampage, together with shattering naval victories won by a legendary Mayo man fighting for the Argentine nation, redrew the map of South America.

It’s strange to think that for all of the violence and social upheaval it has seen, the single worst episode of communal violence ever to hit Rio was caused by a couple of thousand Munster farmers who took a wrong turn. Hundreds of them would never leave Rio again and would fall victim to violence, disease and destitution. Those that survived would be scattered to the four winds, ending up as refugees in Britain or in isolated pockets in South America and the West Indies.

Irish people travelled in their thousands to South America at the end of the eighteenth and start of the nineteenth centuries. Some found fame and considerable fortune, from the Irish who established rancher dynasties on the prairie-lands of Argentina to soldiers and statesmen like Admiral William Brown and Bernardo O’Higgins. But as well as these successes, there were also the ‘forgotten’ Irish of South America, mostly land-hungry Catholics looking for a better life.

Under the Sugar Loaf of Rio de Janeiro in 1827, some of these forgotten Irish men and women became known as ‘escravos brancos’ – the ‘white slaves’.

The reasons for the ‘white slaves’ presence in Brazil date back several years to 1825. The newly-

crowned emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro I (who would become King of Portugal in 1826), was facing a manpower problem, war with his neighbours to the south and dynastic battles with his relations amongst the ruling family of the mother country, Portugal.

In the lingering turmoil of post-Napoleonic Europe, he was fighting to assert his right to the throne of faraway Portugal while striving to build an empire in the vast, fractious territories of Brazil.

The war for the Banda Oriental, modern-day Uruguay, had started well for Dom Pedro thanks to his largely Portuguese troops, who were hardened by years of fighting alongside the British (led by the Irish-born Duke of Wellington) in the brutal Peninsular War against Napoleon.

In the dispute over the territory bordered by the Rio del Plata and the Uruguay River, the Brazilians were fighting against ill-trained and irregular forces of Argentine gauchos who received little or no backing from the government in Buenos Aires. However, the long conflict had worn down the Brazilian forces and many of the Portuguese veterans had returned home, leaving native-born Brazilian soldiers from tropical regions to fight in a desolate and cold wasteland, so by early 1827, the war was not going well for Dom Pedro.

In addition to the problems on land, the Brazilian navy was being pressured by the Argentines, under the command of Mayo-born Admiral William Brown, one of the great heroes of Argentine history. Brown, already a legend of the Argentine war of independence had long warned of the danger posed to Buenos Aires by the Brazilian navy, but had been ignored by the politicians who, forgetting the great service he had already done for their country, dismissed him as ‘a foreigner’.

|

| Admiral William Brown - The Ginger Ninja of The Seas |

Before the battle, the Mayo Man addressed his officers and men, declaring ‘Comrades: confidence in victory, discipline, and three hails to the motherland!’

And as the Brazilian ships came within cannon shot, and thousands of Argentines watched from the shore, the indefatigable Brown shouted; ‘Open fire! The people are watching us!’

After his shattering victories, Brown effectively forced the Brazilians to sue for peace.

When the Irish admiral returned to Buenos Aires, he was greeted by bonfires and wild street

celebrations from a relieved and thankful populace. The Irishman a "foreigner" no more.

Some months before Brown’s victory at sea over Brazil, Dom Pedro realised the tide of the war had started to turn against him; running short of men, material and loyal subjects to colonise the disputed lands, he made plans to encourage European immigration and put a premium on tradesmen, farmers and mercenary soldiers.

After plans to import 5,000 German peasent farmers fell through, Dom Pedro turned to the era’s favoured source for cheap cannon-fodder and expendable colonists – the Irish.

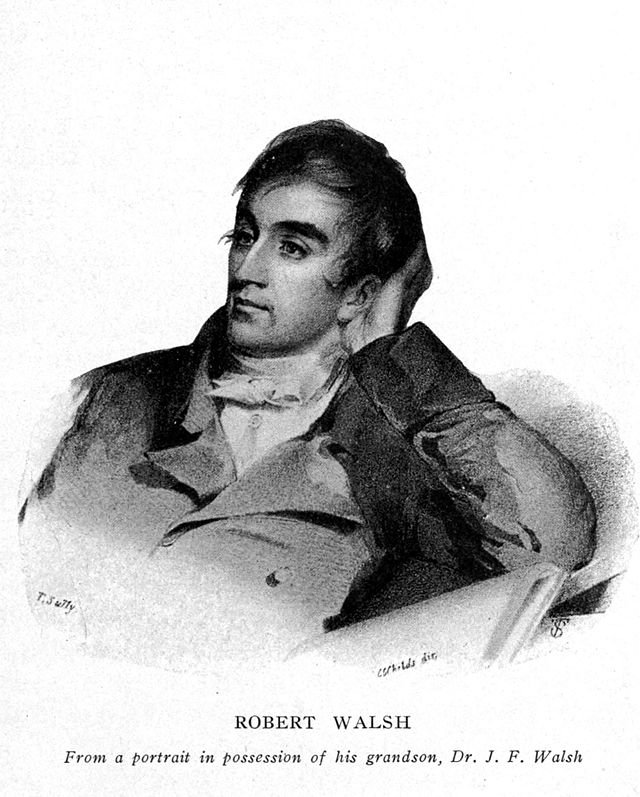

Waterford-born Robert Walsh, was a prominent anti-slavery activist in the US and chaplain to the British embassy in Rio at the time and later wrote that Dom Pedro decided on; ‘the Irish, who from the redundancy of population at home, might be easily procured.’

William Cotter, an Irish-born colonel in the service of the Brazilian army, was despatched to Ireland in October 1826 to start the recruitment process.

Cotter sent out advertising bills across Munster, promising free passage, provisions (including free clothes) and a grant of land in the exciting new country of Brazil for those brave enough to take the opportunity of a lifetime. Advertisements were placed in Irish newsheets and recruitment pitches were read out in Churches and tacked to the walls of country courthouses.

Ominously, a stipulation that some light military service may also be involved was relegated to the small print. Many of the recruiting posters made no mention at all of possible service in the army of the Emperor of Brazil.

Contemporary sources say that many of the men who signed up understood that there would be an obligation to train as militiamen to defend their settlements while others ‘whose idle habits led them to prefer a military life’, freely volunteered for the army.

British embassy chaplain Robert Walsh, who interviewed many of his fellow Irishmen in Rio shortly after their uprising, recorded that many of them had hoped to find a new life in Brazil.

|

| The Irish American Diplomat & Anti-Slavery Campaigner Robert Walsh |

‘The notifications were received with great joy by the people,’ Walsh recorded in his Notices of

Brazil in 1828 and 1829, published in London shortly after his return from South America.

‘The exceeding distress of the poor peasantry of that part of Ireland, as well from exuberant population as want of employment, is notorious, and they were eager to avail themselves of the proposal.

‘Land was the great object of their competition at home, and they who thought themselves fortunate in obtaining a few acres at an exorbitant rent in Ireland, were transported at the idea of receiving a grant of fifty acres, rent free, in Brazil."

‘Many, therefore, as they told me, sold their farms at home, and laid out the small portion of money they could raise, in purchasing agricultural implements, conceiving that their military service was to be merely local, and would no more prevent their attending to their land, than if they were members of yeomanry corps in their own country.

‘Some of them, as was to be expected, were of indifferent characters and dissolute manners; but

the majority decent, respectable people, who brought out with them their wives and families, and

who would be an acquisition to any country as settlers, but particularly to Brazil.’

Colonel William Cotter was a natural born salesman and the ground was more than fertile for his promises of paradise in the New World.

He quickly signed up between 2,400 and 2,500 farmers and their families, almost none of whom had military experience of any kind.

A small armada of ten ships would eventually set sail from Cork to Brazil (for the ports of Rio,

Espirito Santo and Sao Paulo) carrying a total of 3,169 passengers, comprising 2,450 men, 335 women, 123 young boys and girls and 230 children. One ship, the Charlotte Maria, left Cork on 9 September 1827, with two hundred and fifty men, twenty-six women, and nine children on board, arriving in Rio de Janeiro 22 December. A man called William Herbert, perhaps sensing which way the wind was blowing, jumped ship in Tenerife. Thirteen died on board and of the other families, familiar Irish names like Welsh, Leahy, Maher, Hartnett, Daly, McCarthy, O’Leary, Sullivan, Power, Mills and O’Shea (and at this point, a quick howya to the great-great-great-grandad!) were recorded in the ship’s manifest.

The contracts they had signed (even if, in many cases, not fully understood) promised them pay and allowances equal to one shilling per day plus victuals, as well as a grant of forty acres of land after five years of service to the Emperor. The key point was that their military service would be limited to four hours of training each day and while they would be ready to act as a kind of army reserve, the Irish would ‘not be sent out of the province of Rio unless in time of war or invasion’.

They did not know of the bitter, intermittent and drawn-out war that was already being fought on the disputed border between the Argentine and Brazil.

But both parties were about to get a shock. The Irish, on their arrival in Rio and Dom Pedro, who would soon learn that he needed more Munster Men like Custer needed more Indians.

******* Thanks for Reading - The Second and Final Part of Munster Men Go Mad In Rio - is Here

hi

ReplyDeleteapparently col Cotter was my great great grandfathers uncle. So far the oldest relative I can find. What a bastard! sean.hyde12@gmail.com

Hiya,

DeleteThat's very interesting - if you have any details on Cotter - who was a v shadowy character - I would be happy to hear them. The full chapter on the whole debacle is in my book.

Joe

Fascinating, Great read thanks.

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed it - thanks for reading.

DeleteMy great-grandfather told stories about his father going to Brazil from Cork with his Mother & Step-Father and the Irish were forced to join the Brazilian Army. Is there a way to check the ships' manifests for a Dennis Kelleher (my Great-great-Grandfather, Humphrey Murphy was born in 1823 so he would have been 5 or 6 years old)? Wondering if there is some truth to the tales or if Humphrey read about it in a later newspaper and added the tale into our family's history. The family was in Detroit by 1833.

ReplyDelete